By Will Atwater

What type of pollution is so tiny it can be invisible to the naked eye? Hint: Humans ingest it through the air we breathe, the food we eat and the water we drink.

The answer: microplastics.

Microplastics are produced from the breakdown of the millions of tons of plastics — much of it single-use plastic — that clog landfills, choke up waterways and float in the air we breathe.

In 2021, the U.S. generated between 40.1 million and 51 million tons of plastic waste. Of that amount, somewhere between 32 million and 43 million tons ended up in landfills, according to data provided by Statista, a research and marketing firm.

A mounting body of research suggests that plastic waste — some particles are small enough to be inhaled — could harm your health.

The research around the critical need to reduce microplastics is mounting. For a study published in May, researchers in China examined blood clots removed from arteries in the brain and heart and veins in the lower body of stroke patients. The researchers found evidence of microplastics in those arteries and veins, and the researchers documented 15 types of plastic particles and plaque in the tissue samples.

The plastics found were those used to produce a range of products, including food wrap, shopping bags, water bottles, carryout food containers and building materials. Of the different types of plastic particles, polyethylene (PE), polyvinyl (PVC), polystyrene (PS) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET) were among the most common.

These realities are part of the impetus behind the Plastic Free Foundation’s initiative: Plastic Free July, which started in 2011. The foundation’s goal is to challenge people to avoid using any single-use plastic for a month — that’s no disposable plastic forks for eating potato salad, no red plastic cups at the July Fourth picnic, no plastic water bottles at the beach.

While the challenge sounds daunting, according to the foundation, the annual campaign has kept 3 billion pounds of plastic out of the waste stream in the past five years.

Plastic waste and human health

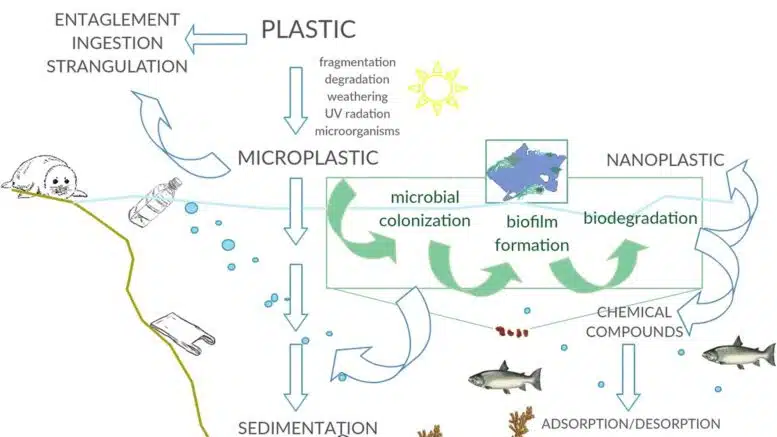

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, microplastic compounds are fragments smaller than 5 mm in length, roughly the size of an eraser on the end of a pencil. However, microplastics can break down into smaller particles invisible to the naked eye, known as nanoplastics. These substances can last hundreds, even thousands, of years in the environment.

These are the plastics found by the Chinese researchers when they dissected the blood clots.

“This is an important observation that these scientists have [made], where they’ve looked at the clots that they’ve taken out of people who had a heart attack or stroke or a clot in their lungs and found these microparticles,” said Manesh Patel, chief of the Division of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Duke University School of Medicine.

Patel added that this research, combined with other studies, “does make us think and worry that environmental exposure could be causing or at least playing a role in some of the adverse chronic heart disease or vascular disease that we see.”

Globally, more than 430 million tons of plastic is produced annually. Some plastics break down into these microplastic particles, and a significant amount of them end up in the ocean, where marine animals swallow them. That’s one way they enter the food chain, according to a report by the United Nations Environment Programme.

In 2023, Duke researchers led a study that revealed a possible link between nanoplastic particles and a brain protein that may result in increased risk for Parkinson’s disease and some forms of dementia.

Previous studies have revealed that humans ingest about a credit card-size amount of microplastics weekly and suggested links between microplastic ingestion in people and inflammatory bowel disease. There’s also some suggestion that microplastics alter how hormones function in the body. What’s more, a study published in June estimates that humans may inhale 74,000 to 121,000 microplastic particles annually.

Combating plastic waste

Activists are driving efforts to reduce the amount of plastic waste that ends up in landfills, waterways and the food system. One effort calls for developing a circular economy, which would involve replacing single-use plastic foodware and utensils used by restaurants, for instance, with reusable cups, plates and knives. Circular economy supporters argue that reducing the production of single-use plastics would limit the amount of plastic waste that enters the environment, thus improving human and animal health.

“We are facing many burgeoning potential health problems and environmental problems coming out all the time [related to] our society’s dependence on plastic and what it’s doing to our bodies and the air and the water and the soil and the wildlife,” said Crystal Dreisbach, CEO of Upstream, an organization that works with companies and institutions to eliminate waste.

Dreisbach and other environmental advocates support extended responsibility laws that would hold product producers responsible “for the end-of-life management of plastic packing […]

shifting the financial and physical burden upstream and away from the public sector or taxpayers,” according to a statement on the National Caucus of Environmental Legislators’ website.

In 2023, a group of North Carolina lawmakers in the state legislature, which included Reps. Deb Butler (D-New Hanover) and Pricey Harrison (D-Guildford), introduced House Bill 279, which includes a section titled “Extended Producer Responsibility.”

The bill died in committee.

Is litigation the way forward for environmental causes?

Patrick Boyle, corporate accountability attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law, makes a case for using litigation as a tool to force plastic producers to take responsibility for addressing plastic waste. Recently, Boyle and his colleagues released a report titled “Making Plastic Polluters Pay: How Cities and States Can Recoup the Rising Costs of Plastic Pollution.”

“The scope of the harm is so broad,” he said. “We do think that as stewards of their citizens’ public health and the natural resources and environments […], that state [attorneys general] and municipal attorneys have a duty as part of their mandate or responsibility to bring these types of cases.”

Adjudicating more environmental issues may become more commonplace as a result of a U.S. Supreme Court ruling in June. In the case Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, the court ruled that federal agencies such as the Environmental Protection Agency would no longer have the authority to use their expertise to interpret ambiguous laws. Instead, judges will assume sole responsibility for doing so.

The ruling affects the Chevron Doctrine, which emerged from a 1984 Supreme Court case between Chevron Corp. and the Natural Resources Defense Council. The court ruled to defer to regulatory agencies when federal regulations were ambiguous, so long as the regulators provided a reasonable interpretation.

Deference to federal agencies by the courts to interpret federal regulations evolved as the world became more complex, said Michelle Nowlin, co-director of the Duke Law and Environmental Policy Clinic.

“Overtime, a refinement of judicial doctrine of how we’re going to implement these laws that are more technical than we can understand without being derelict in our duties to faithfully interpret the laws, [is] how the Chevron Doctrine developed.”

While litigating environmental cases is an option, it is one that seemingly disadvantages low-wealth communities and the nonprofit organizations people in those communities often rely on to represent them in court.

“More litigation favors those who are wealthy, those who have deep pockets. It favors the corporations who have a lot of money that they can draw on,” Nowlin said.

Consumer demand drives corporate responsibility

While it’s unclear how the Supreme Court’s decision to move away from what is referred to as the Chevron Deference will play out, there is hope for environmentalists who are working to reduce plastic waste, in part as a response to consumer demand.

In one small example, Haleon, the company that makes over-the-counter allergy medicine Flonase, has changed the product’s packaging. Until recently, Flonase came in a nonrecyclable plastic case. Now the company has switched to a mostly recyclable package.

“Haleon has set a target to cut their use of virgin petroleum-based plastic by 10 percent by 2025 and by a third by 2030,” said Jeremy Pare, visiting professor of business and the environment, Duke University’s Nicholas Institute of Energy, Environment and Sustainability. “They also aim to develop solutions for all product packaging to be recycle-ready by 2025 with the goal of all packaging recyclable or reusable by 2030,” he added.

While moves like Haleon’s offer hope, Pare said there is more work needed before companies perfect totally recyclable packaging.

“If you notice, even the box, once the safety label is removed, is still not 100 percent recyclable, which means that the package is almost impossible to recycle in most recycling facilities because they cannot separate the plastic from the paper board,” Pare said.

“With a goal for this work by 2025 and 2030, respectively, Haleon may be on to some innovations that will allow this to happen, but we will have to wait and see as the industry needs to mature as a whole on plastic recycling options.”