By Will Atwater

Pender County resident Sharon Mathis recently had her well water tested for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, and she’s not happy with the results.

Mathis is one of thousands of local residents worried about contamination from the chemicals, which had been released by the nearby Chemours plant.

She now has a double hardship. Mathis found out her well water is contaminated, but not enough. This means she doesn’t qualify for remediation support because her well’s contamination level falls short of the health advisory threshold of 10 parts per trillion set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

“My thing is, my water is 6.9 [ppt] and my neighbor’s is 10 [ppt],” she said.

It’s a dilemma. Mathis’ water is polluted, but somehow not enough to merit getting cleaned up.

“My water is still nasty. Why would I want to take a bath in it, why would I want to drink it?” she asked.

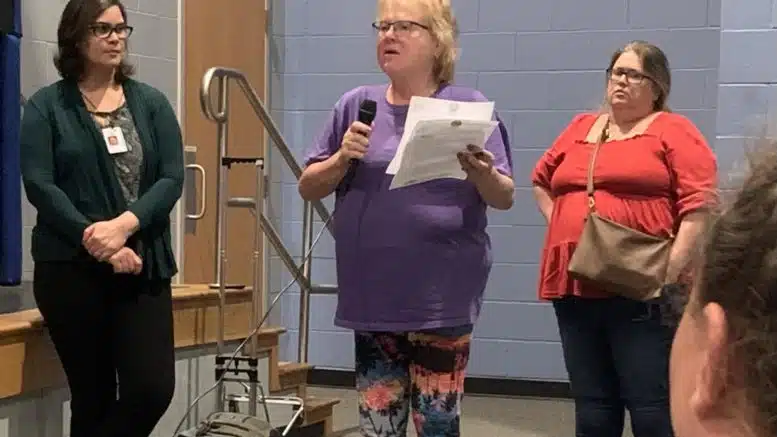

Mathis directed her question to a panel of experts during a recent event that gathered more than 80 local residents to discuss private well water testing for PFAS in Pender County. Officials from the state Department of Environmental Quality and the state Department of Health and Human Services made presentations and took questions for two hours in the auditorium of Heide Trask Senior High School, in the Pender County town of Rocky Point.

Michael Scott, DEQ water resources division director, had walked the audience through a Powerpoint presentation, recapping events that have unfolded since 2017 when GenX, a class of PFAS, was discovered in the Cape Fear River Basin downstream of Chemours’ Fayetteville Works site.

Since the 1940s, PFAS — referred to as “forever chemicals” for their persistence in the environment and the human body — have been used in the manufacturing of oil and water-resistant products, as well as products that resist heat and reduce friction. There are more than 12,000 PFAS compounds used in products such as nonstick cookware, cosmetics, cleaning products, water-resistant clothing and textiles, some firefighting foams and firefighting turnout gear.

While there is no definitive evidence about the health risks PFAS pose to humans, there is mounting research that suggests possible links between extended exposure to forever chemicals and weaker antibody responses against infections in adults and children, elevated cholesterol levels, decreased infant and fetal growth, and kidney and testicular cancer in adults.

In North Carolina, there is mounting frustration among residents who live along the Cape Fear River Basin and have been exposed to PFAS emitted from the Chemours facility. The man-made chemicals are present in the air, soil and water, and many folks who’ve been affected don’t feel that Chemours — or the state and federal governments, for that matter — is doing enough to address the issue.

Arriving at this moment: an abbreviated history

2017: Wilmington’s StarNews reported that the local municipal water supply was contaminated by GenX, a class of PFAS manufactured by Chemours at the company’s Fayetteville Works facility. A year later, Cape Fear River Watch, a nonprofit environmental organization based in Wilmington, sued NC DEQ and Chemours to force the chemical company to stop discharging contaminated water into the Cape Fear River.

2017/2018: North Carolina State University researchers launched a PFAS exposure study. Researchers collected and analyzed 344 blood samples collected from Wilmington residents.

2019: Chemours, NC DEQ and Cape Fear River Watch signed a consent order, which required Chemours, among other things, to develop and execute a PFAS remediation plan for contaminated air, soil and water for the lower Cape Fear River Basin communities that were affected. This area includes New Hanover, Brunswick, Columbus and Pender counties.

2020: PFAS Exposure study was extended to include Pittsboro and Fayetteville residents, who also receive drinking water from the Cape Fear River.

2022: The EPA set a drinking water health advisory for GenX compounds at 10 ppt.

Researchers presented study findings, which, among other things, showed the presence of legacy PFAS (PFOA, PFOS, PFHxS, PFNA) in the blood of Wilmington study participants at a level above the national average.

‘Am I creating a Superfund site?’

As part of a consent order between Chemours and the state of North Carolina and the advocacy group Cape Fear River Watch, the company is required to carry out specific tasks such as drinking water well testing for people who live near the site.

That includes extending testing to one-quarter mile beyond the closest well that has PFAS levels above 10 ppt and annually retesting any wells that were sampled. Additionally, Chemours is responsible for providing clean drinking water options to those who have wells contaminated with GenX compounds above 10 ppt.

At that 10 ppt threshold, options for homeowners include connecting them to the municipal water supply, if feasible, or providing a granular activated carbon whole-house system or a reverse osmosis system to be installed at bathroom and kitchen sinks. Depending on which option works for homeowners, Chemours is required to either pay the water bill or maintain the filtration system for a minimum of 20 years or until PFAS levels fall below the established health advisory threshold.

Even though those requirements have been spelled out for several years, some local people have had their wells tested, while others in the same community are still waiting.

There are several possible reasons that a homeowner may not be eligible to have their well water tested, Scott explained.

“It can be that you don’t meet one of the initial criteria that we shared: proximity to the river, proximity to municipal water and sewer lines, or proximity to another well that’s already been detected,” he said. “It doesn’t mean you’ll never be tested, it means you may not be tested right now on this initial round.”

New Hanover resident Wayne Lewis — whose wife died in 2009 due to a liver condition that doctors couldn’t explain — expressed concerns about PFAS skin and soil absorption.

“I’m putting [water] on my yard and on my garden. Am I creating a Superfund site?” he asked. “Does PFAS go through [the soil]? I’ve got three-quarters of an acre that I’m watering. I don’t want to be eating food that’s absorbing [PFAS].”

More research is needed to answer whether absorption through the skin is a health risk and what impact PFAS-contaminated soil and water may have on garden produce, said Virginia Guidry, who leads the Environmental Health Branch for the NC Department of Health and Human Services.

“There are so many benefits of eating fresh fruits and vegetables, eating things that you grow in your own garden,” she said. “We really want to be very careful about giving guidance that people shouldn’t eat their fruits and vegetables.”

Demanding more

Christine Jarvis, like many who attended the meeting, said she’s worried about the cumulative impact of PFAS on her children, who grew up drinking well water that she said she now knows is contaminated. Jarvis said she’s also concerned about her farm animals, which have succumbed to unexplained illnesses or have died unexpectedly.

In addition to health concerns, Jarvis wants to know what will happen if she decides to move.

“What does [PFAS] do to the value of my property? Are you going to buy property with contaminated water?” she asked.

Scott answered in part by telling her: “We work on a lot of contaminated property that is effectively resold, based on how you limit any exposure to [PFAS] compounds.”

Other issues raised included the concern that, due to supply chain issues, homeowners who qualify may have to wait indefinitely to connect to the municipal water. A Pender County employee who orders materials said that the global supply chain issues are unprecedented.

Dana Sargent, executive director of Cape Fear River Watch, was one of the last audience members to offer a comment, and she, among other points, reminded people to keep demanding more from public officials.

“I’m proud of the Consent Order,” she said. “Cape Fear River Watch sued [Chemours] and DEQ to make it happen, but it was just supposed to be the beginning.”

Close window

Republish this article

- You can copy and paste this html tracking code into articles of ours that you use, this little snippet of code allows us to track how many people read our story.

- Please do not reprint our stories without our bylines, and please include a live link to NC Health News under the byline, like this:By Jane DoeNorth Carolina Health News

- Finally, at the bottom of the story (whether web or print), please include the text:North Carolina Health News is an independent, non-partisan, not-for-profit, statewide news organization dedicated to covering all things health care in North Carolina. Visit NCHN at northcarolinahealthnews.org. (on the web, this can be hyperlinked)

1