By Taylor Knopf

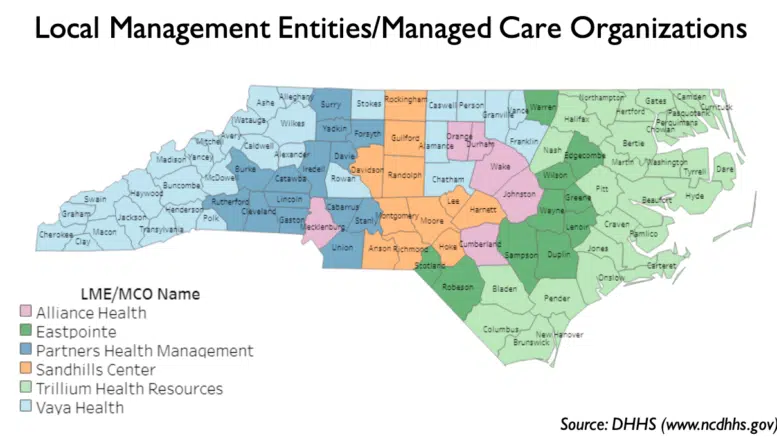

North Carolina’s six local behavioral health management companies — known as LME-MCOs — will see some significant restructuring soon.

For years, patients, their families and mental health advocates have lodged repeated complaints about the lack of services some of the LME-MCOs provide and about the difficulty people have navigating the mental health system. State lawmakers have also had their share of frustrations with trying to hold the organizations accountable when problems arise.

In 2013, North Carolina shifted away from a county-based system to a regional managed care system to deliver behavioral health services to uninsured patients and people receiving Medicaid. At the time, health leaders wanted to better organize the publicly funded behavioral health system and save and use Medicaid dollars more efficiently. But lawmakers have struggled to control the local groups that manage the state dollars and services. When community services began to dry up, the complaints rolled in.

With the rollout of Medicaid managed care plans in 2021, some easier-to-treat mental health patients were rolled onto these new standardized plans, which can handle people with fairly common problems, like depression or anxiety. The folks who have been harder to treat — those with severe and persistent mental health problems, or those with intellectual and developmental disabilities — are slated to go into “tailored plans” which are intended to encompass more targeted, intensive services.

But the rollout of those tailored plans has been delayed multiple times.

State lawmakers have expressed disappointment at these delays. There have also been long-standing issues with how the LME-MCOs have provided mental health services to children in foster care — at times putting up roadblocks to vulnerable kids getting the help they needed.

The state budget passed by the General Assembly last month includes a large section of policy changes about the LME-MCOs —changes that ultimately give the secretary of the state’s Department of Health and Human Services more control and oversight of the groups. Secretary Kody Kinsley said his department is already working on how to restructure the groups so they can focus on what they do best.

As mental health advocates wait to see how DHHS will restructure the groups, Disability Rights NC Director of Public Policy Corye Dunn said she is eager to see the publicly funded mental health system simplified to offer greater choice to people with disabilities. Her organization works to ensure better care for those with mental illness and disabilities.

Reducing the number of LME-MCOs

“We have to improve the services that the LME-MCOs provide,” Rep. Donny Lambeth (R-Winston Salem) told NC Health News in an interview. “I get more complaints locally in my district about the lack of services that the LME-MCO provides here than any other probably single topic outside of maybe teacher issues.”

Lambeth said he didn’t think that some of the LME-MCOs would be financially viable enough to survive in the long term, and that there should be a reduction in the number. Originally, there were 11 across the state, but after the failure of one of the largest organizations in the western mountains, the state pushed many of the organizations to consolidate. Now there are six, and two of them recently announced they would merge.

“I would tell you that we spend a disproportionate amount of time during the [state budget] conference process talking about the LME-MCOs,” Lambeth said. “We weren’t completely convinced that we had the right solution.”

Lambeth said lawmakers got significant pushback from the LME-MCOs when they discussed reducing the number of groups during the budget negotiation period.

“There are some LME-MCOs that provide great services. People in those districts love the LME-MCO that serves them, and they just didn’t want to change,” Lambeth added. “Change is often hard, and that’s what we were up against.”

As legislative budget negotiations wrapped up last month, Lambeth said lawmakers decided that it would be best to give the secretary of DHHS the responsibility of deciding how many LME-MCOs there should be and how they should be structured.

Dunn of Disability Rights said that having “an excessive number” of LME-MCOs in North Carolina’s system has caused problems for people with disabilities since the state switched to a managed care model.

“It has created barriers to accessing care, decimated the network of available providers, and wasted money and other resources to staff duplicative functions across the state,” Dunn said. “Meanwhile, people who relied on those MCOs to access care were stuck with whatever agency they were assigned based on geography alone, the only population in our system with no choice of managed care entity.”

Lawmakers want specific changes

Sen. Jim Burgin (R-Angier) told NC Health News that he was “really disappointed” when the LME-MCOs continued to delay the launch of the tailored plans, saying he doesn’t believe that they all “see the urgency.”

The tailored plans are designed for individuals who require more extensive care and support than the average person with Medicaid coverage. Some uninsured people who used to receive care through the LME-MCOs will now qualify for Medicaid, shifting to those standardized plans. But the remaining people are those who will require intensive management and more resources.

“The LME-MCOs deal with the most fragile people in our society,” Burgin said. “When you’re talking about that population, you can’t get that wrong.”

“We feel like the secretary is closest to the situation to make those tough decisions,” he added. “This is not something that he’s doing in a vacuum. We’ve all been talking about this and worrying about it and praying over it, trying to get it right. But we feel like we are heading toward a direction to get where they will be responsive and accountable to all the citizens.”

With these changes to the LME-MCOs’ responsibilities, Burgin said state lawmakers want to see a successful launch of the tailored plans. Some of the LME-MCOs say they are ready to move forward.

“Successfully launching these integrated health plans to better serve our members and their families is our primary goal, and we support updates to the public system that will promote continuity of care for members and stability for our providers and community partners,” said Brian Perkins, senior vice president or strategy and government relations at Alliance Health, the LME-MCO that serves the Triangle area, as well as Cumberland and Mecklenburg counties.

“Alliance Health fundamentally believes that a public managed care system is best for North Carolina individuals…” Perkins continued in an emailed statement to NC Health News. “Throughout the state budget negotiations, it was encouraging to know that many NC policymakers share this belief and directed that the public system be restructured to ensure the ability and sustainability of LME/MCOs that will launch and operate Tailored Plans by July 1, 2024.”

Joy Futrell, CEO of Trillium Health Resources — which serves the easternmost counties in the state — said she was “pleased to see long-term commitment” from the General Assembly to the public health system and the tailored plans.

“We hope to work collaboratively with new providers and stakeholders to start serving residents soon to minimize confusion and ensure continuity of care for our members and recipients,” she said.

In addition to the launch of the tailored plans, Burgin said state lawmakers want to see an improved Medicaid plan for children and families involved in foster care. The LME-MCOs have been responsible for providing services to this population and have come under criticism for high-profile failures that include children with mental health needs living in emergency rooms and sleeping on the floors of social services offices.

The state budget included the creation of a statewide specialty Medicaid plan for kids in foster care and their families that aims to integrate their physical and mental health care. The LME-MCOs have pushed back against similar proposals for years.

The state budget directs DHHS to issue requests for proposals from agencies that wish to hold the contract for the statewide foster care plan, with the new services set to begin by December 2024.

As a result of these budget policy changes, Kinsley and his team at DHHS will now have more authority over the mental health services provided to the most vulnerable North Carolinians.

More authority to DHHS

“We’re putting a big burden on the secretary, but he knows we are here to help him and to get this right,” Burgin said. “This is a really big deal, and we’re all going to be focused on it.”

The conversations about restructuring the LME-MCOs and holding them accountable to the people they serve has been going on for a while, Kinsley said, adding, “it is great that we have drawn the line and that we have now moved forward.”

Sign up for our Newsletter

“*” indicates required fields

DHHS is the exclusive payer of the services the LME-MCOs provide.

“It allows me as the payer … to be able to hold one entity accountable for a very focused mission for a very small population,” Kinsley said. “When you speak to folks across the state, everybody’s happy with something the LME-MCOs are doing. For me, trying to hold them accountable to the things that they’re not doing has been a struggle because they’ve also, by law, got contracts regardless of their performance.”

Kinsley said his department is already analyzing the current LME-MCO system and will be “moving rapidly” to make decisions on how to restructure them so that “everybody can specialize and focus” and ultimately “improve the system.”

The LME-MCO that represents the far western counties, Vaya Health, said in an emailed statement that the organization is confident the secretary will take thoughtful consideration and “make the best decision for members, families, providers and counties to further strengthen the public behavioral health system and successfully launch the tailored plans.”

As more responsibilities flow to the state health department, Kinsley said he still needs more financial investment in his administrative team to run it all.

At the same time, he explained that a lot of the work the department does to get grants out to community partners is built on existing strategies that can be scaled up. He also applauded the rate increases state lawmakers provided in the state budget for those working in state-run psychiatric facilities and some block grant money to hire more people to manage grant contracts.