By Will Atwater

Undeterred by the sweltering heat on the grassy mall behind the legislative building in Raleigh on July 10, Democracy Green’s co-founder and executive director Sanja Whittington stepped to a microphone and delivered an impassioned plea.

“We are calling upon the Environmental Management Commission to vote yes to removing PFAS from our drinking water sources today,” Whittington said. ”Our bodies weren’t created to consume and digest toxic cancer-causing chemicals such as PFAs and other emerging contaminants.”

Democracy Green, an environmental advocacy group, organized the news conference, which was livestreamed on the group’s Facebook channel one hour before the North Carolina Environmental Management Commission’s Groundwater and Wastewater Committee meeting.

Nearly 30 people, including community residents and local officials, endured 95 degree heat to support the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality’s recommendation to establish surface and groundwater standards for eight PFAS.

After the news conference ended, the focus shifted to the nearby Archdale Building, where the Environmental Management Commission committee met in the afternoon to listen to the presentation by DEQ staff members and decide whether to move forward with the agency’s recommendation to the entire commission, which calls for establishing health-based standards for eight PFAS: PFOA, PFOS, GenX, PFBS, PFNA, PFHxS, PFBA and PFHxA.

After a lengthy discussion, in a move that surprised some, the Groundwater and Waste Management committee voted to have the DEQ staff present a revised regulatory impact analysis for just three PFAS — PFOA, PFOS and GenX — to the Environmental Management Commission for regulatory consideration in September.

Robin Smith, an environmental lawyer and previous assistant secretary for environment at the former North Carolina Department of Environment and Natural Resources, posted the following response to the committee’s decision on her SmithEnvironment Blog:

“It was difficult to discern from the discussion any clear rationale for the recommendation to abandon adoption of health-based standards for the other five PFAS when those standards would have provided greater clarity on health risk; reduced the regulatory burden on business; and protected property values.”

Forever chemicals

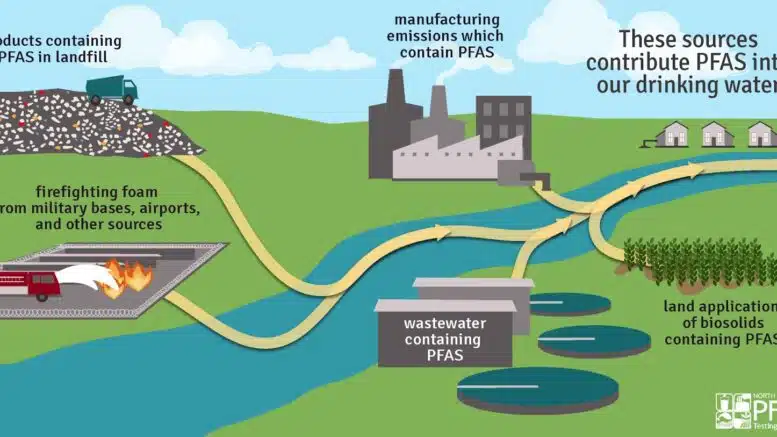

PFAS or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as “forever chemicals”

for their potential to persist in the environment for thousands of years, comprise nearly 15,000 compounds, according to CompTox, a chemical database maintained by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The compounds are used in hundreds of industrial, commercial and consumer products, such as nonstick cookware, makeup, moisture-repellent garments, fast-food wrappers, firefighting protective gear and some firefighting foams.

PFAS accumulates in people’s bodies, and researchers have found evidence that suggests links between PFAS exposure and an expanding list of adverse health impacts, such as weaker antibody responses against infections, elevated cholesterol levels, decreased fetal and infant growth, childhood obesity and kidney cancer in adults.

The conversation about PFAS began to take hold in North Carolina in 2017, when GenX, a class of PFAS manufactured at the Chemours’ Fayetteville Works facility, was discovered in the Cape Fear River.

PFAS contamination timeline

[2017: Wilmington’s StarNews reported that the local municipal water supply was contaminated by GenX, a class of PFAS manufactured by Chemours at the company’s Fayetteville Works facility. A year later, Cape Fear River Watch, a nonprofit environmental organization based in Wilmington, sued N.C. Department of Environmental Quality and Chemours to force the chemical company to stop discharging contaminated water into the Cape Fear River.

2017/2018: N.C. State University researchers launched a PFAS exposure study. Researchers collected and analyzed 344 blood samples from Wilmington residents.

2019: Chemours, N.C. DEQ and Cape Fear River Watch signed a consent order, which required Chemours to, among other things, develop and execute a PFAS remediation plan for contaminated air, soil and water for the lower Cape Fear River Basin communities that were affected. This area includes New Hanover, Brunswick, Columbus and Pender counties.

2020: PFAS Exposure study was extended to include Pittsboro and Fayetteville residents, who also receive drinking water from the Cape Fear River basin.

2022: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency set a drinking water health advisory for GenX compounds at 10 parts per trillion.

2023: A U.S. district judge certified two class-action suits that include water utility customers and private well water owners who live near the Chemours Fayetteville Works facility.

The EPA grants Chemours permission to import up to 4 million pounds of PFAS waste from the Netherlands to its Fayetteville Works facility.

Researchers discover 11 previously unknown PFAS compounds in the Cape Fear River.

2024: The EPA announces drinking water standards for six PFAS: PFOA, PFAS, HFPO-DA (GenX), PFBS and PFNA.

A N.C. Newsline article identifies companies other than Chemours that have discharged PFAS into N.C. waterways.

July 10: The N.C. Environmental Management Commission Committee voted to move forward with a recommendation that the full EMC consider surface and groundwater standards for three of eight PFAS recommended by N.C. DEQ. Those compounds are PFOA, PFOS and GenX.

Who’s affected?

The day before the Environmental Management Commission committee met, organic farmer owner Ty Jacobus, who lives in Castle Hayne, a village in New Hanover County, raised a question that has undoubtedly been on the minds of many North Carolinians dealing with drinking water contaminated by PFAS:

“We now have these chemicals in all of our aquifers, our food supply and our drinking water indefinitely,” Jacobus said. “What does that do for our children, grandchildren and generations down the road that will be left with this problem?”

Jacobus made these remarks during a Zoom call organized by the National Resource Defense Council, which was livestreamed on the Cape Fear River Watch Facebook page. The call was attended by members of the media, who heard from Jacobus and business owner Steven Schnitzler, as well as representatives from environmental organizations, including Clean Cape Fear.

As with Democracy Green’s news conference, Natural Resources Defense Council and its partners organized the call to spread awareness about what it and others see as imperative: that North Carolina lawmakers pass PFAS standards for surface and groundwater comparable to the federal standards that now exist for the municipal water supply.

In April, North Carolina Health News reported that the EPA established enforceable maximum contaminant levels of 4.0 parts per trillion for PFOA and PFOS. Maximum contaminant levels represent the highest levels of contaminant allowed in drinking water under the Safe Drinking Water Act. North Carolina’s current maximum contaminant level for PFOA and PFOS is a combined 70 parts per trillion.

In 2022, there were roughly 10 million North Carolina residents who received water from public water systems, and 36 percent of them had drinking water above the maximum contaminant levels for PFAS set by the EPA. What’s more, nearly 800,000 other North Carolinians relied on private wells. Of that amount, some 200,000, or 25 percent, had contamination that exceeded the maximum contamination levels for PFAS, according to data provided by the NC DEQ.

Limited relief for well owners

Under the consent order, established in 2018 when Cape Fear River Watch, an environmental advocacy group based in Wilmington, sued Chemours for discharging GenX chemicals into the Cape Fear, well owners may qualify for relief. Also under the order, those who live within a certain geographic area and whose water supply exceeds the federal standards for GenX compounds may qualify to receive bottled water for up to 20 years, or they may receive a granular activated carbon filtration system for their well or a whole house system.

Additionally, North Carolina residents whose wells are contaminated with PFAS may qualify for assistance under the Bernard Allen Fund if they meet certain criteria.

Meanwhile, Jacobus, whose well water contamination was determined to be from a source other than Chemours, has thus far shouldered the cost of treating his water. In June, Jacobus told NC Health News that in 2022, his business suffered a major setback when he discovered that his well water was contaminated with PFAS levels that exceeded the EPA standards, and the produce was also contaminated. Jacobus shared this information again during the Zoom call.

“What it meant for us is that we had to essentially cease operations entirely,” Jacobus said. “We didn’t know at the time what percentage of these chemicals were getting into our produce. A lot of our produce is grown in a greenhouse, and that’s 100 percent well water fed. All of our livestock is fed with well water.”

Jacobus said that because of the setback, the farm didn’t sell produce in 2023, and in this year he learned that the filtration system he installed didn’t remove PFAS, which meant no produce sales for 2024. However, he installed a new filtration system and believes he’s on the right track.

The Environmental Management Commission meets in September and will decide whether to move forward with the surface and groundwater committee’s recommendation and then solicit public comment.

As Democracy Green’s news conference continued, Brunswick County resident and leader Evelyn Johnson offered a reminder of what the ongoing battle against PFAS has cost her community.

“A lot of these people are on fixed income and now have the added expense of purchasing water for basically everything … We can’t afford it. We just can’t afford it.” She added, “Where I come from, fish is a two to three week meal staple, because we get it fresh from the water, [but] even the fish are now contaminated.”

PFAS info box

PFOA – Perfluorooctanoic acid, also known as C8, is produced and used as an industrial surfactant, which helps things not to stick to one another in chemical processes. It also is a raw material for other forms of PFAS. PFOA was widely manufactured but has largely been phased out of production.

PFOS – Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid was a key ingredient in Scotchgard before being banned by the European Union and Canada. Several U.S. states have banned the chemical, derivatives of which were also used in cosmetics. The EPA announced in 2021 that it would regulate the presence of PFOS in drinking water.

GenX – is a derivative salt of hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid (HFPO-DA) and was manufactured by Chemours. It’s the substance initially found contaminating the Cape Fear River in 2017. GenX has been used widely in food wrappings, paints, cleaning products, nonstick coatings and some firefighting foams.

PFBS – Perfluorobutanesulfonic acid is a member of the PFAS family that has been found to have a shorter half life in humans than other similar compounds. It has been used as a replacement for PFOA in Scotchgard despite being listed as a Substance of Very High Concern by the European Chemical Agency.

PFNA – Perfluorononanoic acid is a surfactant, a substance that reduces the surface tension of water, allowing water-repellent liquids (like oils) to mix with liquids that are water-based. Soap is a basic surfactant that allows for dirt to detach from surfaces. PFNA has been widely used as a base chemical for the production of other chemicals in industry to create commercially useful surfactants.

PFHxS – Perfluorohexane sulfonate is also a surfactant and a compound that has been used as an ingredient in stain-resistant fabrics, firefighting foams and food packaging. Once manufactured by 3M, PFHxS use has been phased out in the U.S.

PFBA – Perfluorobutanoic acid was widely used in manufacturing photographic film. It was made by 3M, but the company phased out production of the chemical in the late 1990s. However, the chemical is often formed by the breakdown of other PFAS, and it is persistent in the environment. According to the Minnesota Department of Health, the chemical dissolves more easily in water than other PFAS, allowing it to “move faster in the environment and may contaminate large areas of groundwater.”

PFHxA – Perfluorohexanoic acid is a substance that’s been labeled as a “safer” alternative to some older PFAS for use in manufacturing. Nonetheless, it has been found to induce cellular changes in the liver and skin of mice, as well as affecting gene expression that could affect the immune system.