Editor’s note: This article references self harm and suicide. Please use caution when reading. There are several mental health support resources listed at the end of this article.

By Taylor Knopf

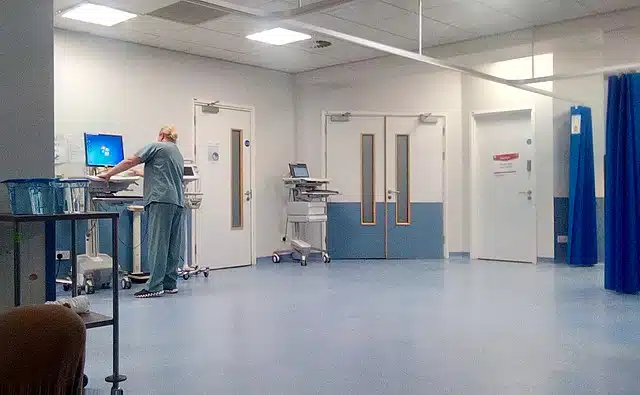

When a loved one is experiencing a mental health crisis, families often go to their local emergency room for help.

This can set off a cascade of events that most people are unaware of and, quite frankly, blindsided by. NC Health News regularly receives emails and calls from families in different stages of this process who are either in shock about what’s happening or angered by the treatment — or lack of treatment — their loved one is receiving.

Family members often feel helpless. As health journalists, we often find ourselves answering their questions about the mental health system and explaining the applicable state and federal laws so people know what to expect — and what is and isn’t normal. For these families and individuals, being armed with information demystifies the process and helps them make informed decisions when advocating for themselves and their loved ones during a mental health episode.

This article attempts to explain North Carolina’s mental health laws as they are written. However, mental health legal experts and advocates routinely hear from people across the state whose experiences do not reflect the allowances under state law.

The law can be nuanced and complicated, and medical providers and law enforcement officers are not always aware of all of the provisions. North Carolina’s mental health laws are contained in General Statutes Chapter 122C. It’s a long statute with many subsections, several of which are referenced throughout this article.

The contents of this article are not intended to substitute for medical or legal advice.

NC Health News would like to thank mental health legal expert Mark Botts, associate professor of public law and government in the School of Government at UNC Chapel Hill, for his consultation and guidance on this article.

Is the patient a danger to themselves or others?

One key factor that hospital staff will determine when a patient shows up in their emergency room in mental health distress is whether the patient is a danger to themselves or others.

The definition of “danger to self or others” is outlined in North Carolina state law under General Statute 122C-3(11) as someone who has recently demonstrated behavior that falls into one of the following descriptions:

- Being “unable, without care, supervision, and the continued assistance of others not otherwise available, to exercise self-control, judgment, and discretion in the conduct of the individual’s daily responsibilities and social relations, or to satisfy the individual’s need for nourishment, personal or medical care, shelter, or self-protection and safety. There is a reasonable probability of the individual’s suffering serious physical debilitation within the near future unless adequate treatment is given… A showing of behavior that is grossly irrational, of actions that the individual is unable to control, of behavior that is grossly inappropriate to the situation, or of other evidence of severely impaired insight and judgment shall create a prima facie inference that the individual is unable to care for himself or herself.”

- “The individual has attempted suicide or threatened suicide and that there is a reasonable probability of suicide unless adequate treatment is given.”

- “The individual has mutilated himself or herself or has attempted to mutilate himself or herself and that there is a reasonable probability of serious self-mutilation unless adequate treatment is given.”

The definition of “danger to others” is also outlined in state law under General Statute 122C-3(11) as someone who has recently:

- “inflicted or attempted to inflict or threatened to inflict serious bodily harm on another, or has acted in such a way as to create a substantial risk of serious bodily harm to another, or has engaged in extreme destruction of property; and that there is a reasonable probability that this conduct will be repeated. Previous episodes of dangerousness to others, when applicable, may be considered when determining reasonable probability of future dangerous conduct. Clear, cogent, and convincing evidence that an individual has committed a homicide in the relevant past is prima facie evidence of dangerousness to others.”

An emergency room provider will examine the patient, keeping these criteria in mind. This is often referred to as the first mental health exam.

Who does the first mental health exam?

People often expect the first mental health exam to be performed by a psychiatrist, but that’s not always the case. In 2019, a state law went into effect that allows other health workers to do first examinations of mental health patients, including social workers, physician assistants and certain nurse practitioners.

The 2019 law also included the creation of a screening tool for the first examination to help health providers direct patients to proper care. There is a flow chart to help determine if the patient’s symptoms are the result of a behavioral health issue, physical issue or a combination of both. Sometimes physical health issues can lead to symptoms that look very much like those of a mental illness. It’s the first examiner’s responsibility to rule out those possibilities.

If a health provider determines the patient is a danger to themselves or others, they will very likely pursue an involuntary commitment.

What is Involuntary Commitment (IVC)?

In North Carolina, anybody can petition a judge to order an involuntary commitment. Because state law (General Statute 122C-201) encourages voluntary admission over involuntary commitment, involuntary commitment is a legal tool that is supposed to be used as a last resort to get someone psychiatric treatment when they are considered to be a danger to themselves or others. These patients temporarily lose the right to make their own decisions while being treated under a court order for psychiatric problems or substance use.

View a blank template of an involuntary commitment custody order here.

The process also supersedes the rights of a parent or guardian to make health decisions for their child — a reality that sometimes comes as a surprise to parents who bring their children to a hospital emergency room.

The following attempts to answer the common questions NC Health News receives from family members of loved ones going through the involuntary commitment process. For a more detailed breakdown of North Carolina’s involuntary commitment laws, check out the explanation linked here by Mark Botts of UNC Chapel Hill’s School of Government.

Read more on the process that unfolds after a judge issues an involuntary commitment order and the next steps when a health provider requests a commitment order for a patient.

What are the rights of a parent or guardian when a child is involuntarily committed?

The rights of a parent or guardian are very limited when a patient is under involuntary commitment. North Carolina law has many allowances for patients admitted to psychiatric care voluntarily, but that changes when the hospitalization is involuntary. For example, if a patient is admitted voluntarily, the “legally responsible person” has the right to consent to or refuse any treatment for the patient (General Statute 122C-57(d)).

Further, before a minor voluntarily admitted to a psychiatric facility can be discharged from treatment, the facility must provide “notice to and consultation with the minor’s legally responsible person” (General Statute 122C-57(d1)). However, no similar notice or consultation is required when the minor is being discharged from involuntary commitment.

For patients receiving treatment under an involuntary commitment, the parent or guardian still retains the right to consent to treatment, but treatment may be given over the objections of the patient, their parents/guardian or health care power of attorney if the physician thinks it’s necessary as outlined in General Statute 122C-57(e). The only exceptions to this — which require written consent of the patient or their guardian — are electroshock therapy, use of experimental drugs/procedures, or surgery other than emergency surgery.

With voluntary admissions and involuntary commitments, the parent or guardian of the patient must be informed in advance of the potential risks and alleged benefits of the treatment choices (General Statute 122C-57(a)).

Even when a hospital emergency department initiates the involuntary commitment process, the parent or guardian still has a right to confidential treatment information regarding their minor child or the individual under guardianship. There is no reason, grounded in privacy law, for the hospital to stop consulting with the parent or guardian about the patient’s care simply because an involuntary commitment process has begun (General Statute 122C-53(d)).

Voluntary admissions to inpatient psychiatric care are possible, but often hospitals default to involuntary admissions for a myriad of reasons that are not grounded in state law, some of which NC Health News outlined in past reporting. Those reasons include:

- For secure transportation — it may be perceived as preferable for the patient to be transported to a psychiatric facility by law enforcement.

- ER physicians often perceive that it’s easier to get a patient admitted to a psychiatric facility if that patient has been involuntarily committed.

- Providers also often perceive that involuntarily committing a patient reduces their liability.

The processes for voluntary psychiatric admissions are outlined in General Statute 122C-211.

The law states that if the patient is a minor or “incompetent” adult, the parent or guardian should be notified of “each instance of an initial restriction or renewal of a restriction of rights and of the reason for it” (General Statute 122C-62(e)).

What are the rights of a patient under involuntary commitment?

The rights of a patient admitted to a psychiatric facility are outlined in NC General Statute 122C-51 through 122C-61. These statutes include rights for those admitted voluntarily and involuntarily. Some overlap, some do not.

“These rights include the right to dignity, privacy, humane care, and freedom from mental and physical abuse, neglect, and exploitation. Each facility shall assure to each client [patient] the right to live as normally as possible while receiving care and treatment,” the law states. “Each client has the right to an individualized written treatment or habilitation plan setting forth a program to maximize the development or restoration of his capabilities.”

Patients also have the following rights during their psychiatric hospitalization:

Sign up for our Newsletter

“*” indicates required fields

- The right to confidentiality with a long list of exceptions outlined in G.S. 122C-53 through 122C-56.1, including for law enforcement investigations and court hearings.

- The right to be “free from unnecessary or excessive medication. Medication shall not be used for punishment, discipline, or staff convenience.”

- Patients may not be subjected to corporal punishment.

- A patient should only be put in restraints or seclusion “when there is imminent danger of abuse or injury to the client or others, when substantial property damage is occurring, or when the restraint or seclusion is necessary as a measure of therapeutic treatment.” If this happens, patients should be frequently observed with written documentation.

- The right to treatment for and prevention of physical ailments during their psychiatric hospitalization.

- The right to send and receive sealed mail and have access to writing material, postage, and staff assistance when necessary.

- The right to contact and consult with, at their own expense and at no cost to the facility, legal counsel, private physicians, and private mental health, developmental disabilities, or substance abuse professionals of their choice.

- The right to contact and consult with a patient advocate if there is one.

- The right to make and receive confidential phone calls.

- The right to receive visitors between 8 a.m. and 9 p.m. for a period of at least six hours daily, two hours of which should be after 6 p.m.

- The right to be outdoors daily and have access to facilities and equipment for physical exercise several times a week.

- The right to keep and use personal clothing and possessions, unless the patient is being held to determine capacity to proceed. The latter are patients who were arrested for a crime but need psychiatric treatment in order to become competent enough to stand trial before a judge.

- The right to participate in religious worship.

- The right to keep and spend a reasonable sum of their own money.

- The right to retain a driver’s license.

- The right to access individual storage space for their private use.

How long do patients wait in the E.R. to go to a psychiatric facility?

The amount of time a patient can wait in the emergency room for an available psychiatric bed varies greatly. Some patients only wait in an emergency room for a day or two, while others wait for weeks or months for an available psychiatric bed that can meet their needs.

The state Department of Health and Human Services publicly reports the average amount of time patients wait for a bed at one of its three psychiatric facilities. For example, in March 2023, the average wait time for a total of 126 patients was 12 days for entry to one of the state’s psychiatric facilities. Meanwhile, in September 2022, the state reported that one patient waited 61 days in an emergency department for a bed in one of its facilities.

The wait times are constantly fluctuating and can be hard to predict.

Not all patients go to one of the three state-run hospitals. There are many private facilities and acute care hospitals with psychiatric inpatient beds, as well, and those wait times are not publicly available.

A patient under involuntary commitment is typically sent to the first facility with an opening. Unlike with voluntary admission, patients and/or their guardians do not get to choose which facility they go to. Sometimes the first available spot is a several-hour drive from their home.

Unfortunately, some patients wait in the emergency room a long time before being transported to a place where they can get treatment for the psychiatric condition that provides the legal basis for holding them involuntarily. However, in some cases, the patient’s condition may improve during their wait in the E.R., and they can be discharged. State law says that if the emergency room staff determine at any time during the waiting period that the patient is no longer dangerous to others or themselves, then the emergency department is required to discharge the patient and terminate the involuntary commitment process (G.S. 122C-263(d)(2)).

If family members, parents or guardians of the patient can use this period of time to demonstrate that inpatient commitment is not needed because the patient can be safely released back home with adequate supervision from family, friends or an outpatient treatment provider, then the patient may no longer meet the criteria for involuntary commitment. Arranging for outpatient psychiatric care, or having an existing outpatient treatment provider consult with emergency room providers, can be influential in some cases.

How is a patient under involuntary commitment transported between medical facilities?

In most cases in North Carolina, a patient under an involuntary commitment is transported from the hospital emergency room to an inpatient psychiatric facility by law enforcement officers.

Officers frequently transport patients in handcuffs — and sometimes ankle shackles — in marked police cars or vans. Patients and their families are often shocked by the arrival of law enforcement officers in their hospital room. They’re usually even more upset by the use of handcuffs, which they say stigmatizes mental illness.

Counties are responsible for providing secure transportation for psychiatric patients under a commitment order, according to state law (General Statute 122C-251). In the majority of the state’s counties, this responsibility falls to the local sheriff’s department and/or police department. North Carolina counties were given the chance to rethink law enforcement transport of psychiatric patients in response to a law that went into effect in 2019. However, the majority of counties opted for minimal to no reform. A handful of counties chose to contract with private transportation companies or EMS instead of using law enforcement.

Meanwhile, North Carolina sheriffs have collectively said they do not want the role of transporting psychiatric patients. They say it takes up valuable resources that could be directed elsewhere and that they believe mental health professionals would be better suited for the role. The routine practice of shackling mental health patients for transport has come under scrutiny from lawmakers on both sides of the aisle, and recently, Gov. Roy Cooper proposed a statewide transportation service for mental health patients.

State law says “to the extent feasible” that law enforcement officers should dress in plain clothes and travel in unmarked vehicles when transporting mental health patients (General Statute 122C-251(c)). Officers should also tell patients that they are not under arrest and have not committed a crime, according to state law. “To the extent feasible,” the law enforcement officer should be the same sex as the patient unless the officer allows a family member to accompany the patient.

The law allows for law enforcement officers to use “reasonable force to restrain” the patient if it appears “necessary to protect” the officer or others. The law states that officers should use every effort to avoid restraining children under 10 years old unless necessary. But it still happens.

Can I transport my loved one instead of the police?

One seemingly unknown allowance under state law is that a clerk, magistrate or district court judge can authorize either a health care provider of the patient or a family member or friend of the patient under involuntary commitment to transport them instead of law enforcement officers. The health provider, family member or friend may request to transport a patient by submitting a form (linked here) to the clerk’s office. Hospital staff and magistrates do not usually tell family members about this option and will not authorize it without a specific request.

“This authorization shall only be granted in cases where the danger to the public, the health care provider of the respondent [mental health patient], the family or friends of the respondent, or the respondent himself or herself is not substantial. The health care provider of the respondent or the family or immediate friends of the respondent shall bear the costs of providing this transportation,” the law states (General Statute 122C-251(f)).

What are the next steps of the involuntary commitment process?

- Second mental health exam

Within 24 hours of arrival at a psychiatric facility, the patient must see a health provider for a second mental health examination to determine if they still meet the criteria for treatment under involuntary commitment.

The second exam in the involuntary commitment process must be administered by a different provider than the one who performed the initial examination, and it can be done in person or through a telehealth visit (General Statute 122C‐266). If the patient no longer meets the criteria for involuntary commitment, the provider must release the patient or they can recommend treatment under outpatient commitment (a process outlined under General Statute 122C-267).

The law dictates that a patient being held under an involuntary commitment must go before a judge in a district court hearing within 10 days of being taken into custody (General Statute 122C-268).

The state appoints an attorney to represent the patient during their involuntary commitment hearing, but a patient can also secure their own legal counsel. The state-appointed legal counsel only represents the patient, not their family. Parents and guardians can request to be present during these hearings, however, there is nothing in state law that dictates the parent/guardian has the right to be present or notified of the hearing itself. The law only states that parents/guardians should be informed of the decision made at the hearing.

If the judge finds there is clear evidence that the patient is a danger to themselves or others, the judge may order the patient to a maximum of 90 days of treatment (General Statute 122C-271). The health provider doesn’t always recommend the maximum time. If the judge finds the patient does not meet criteria for involuntary commitment, they must order the patient’s release.

The decision of the court is final, and a commitment cannot be stayed by an appeal. However, an appeal can be made (General Statute 122C-272).

If requested, supplemental commitment hearings must be scheduled within 14 days of a request for one.

- Discharge from psych hospital

If the health provider at the psychiatric facility determines the patient no longer meets criteria for inpatient commitment, they must release the patient at any time without another court hearing (General Statute 122C-277).

When a patient is discharged from a psychiatric facility, the law states that law enforcement officers from the county where the patient lives are responsible for transporting the patient home (General Statute 122C-251). However, the patient is also able to arrange their own transportation home.

What can you do when something isn’t right?

If you or your loved one is experiencing something you believe is wrong, advocates say you should take notes throughout your interactions with the health facility staff. And always request and save your health records.

Under the federal HIPAA Privacy Rule and the state mental health law (General Statute 122C-53(d)), in most circumstances, parents and guardians have a right to the health and mental health records of a minor or person under their guardianship. It’s also just good practice to take notes about your health encounters and save your records to ensure there aren’t insurance billing errors later.

If you feel something is off about your experience, you can record your conversations with health providers. North Carolina law (General Statute 15A-287) only requires one party participating in a conversation to consent to audio recordings, meaning you can record your conversations without the second person’s consent.

To file a complaint about a health care facility in North Carolina, contact the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services complaint intake unit here, or call the complaint hotline at 919-855-4500.

If you experienced a problem with the involuntary commitment process itself, you can make a complaint to the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services by emailing [email protected] or calling 919-715-2147.

You can also make a complaint at the health care facility in question by asking for the patient advocate or patient relations department.

If a crime, such as assault or sexual assault, occurs within a health facility, file a report with local law enforcement in addition to a complaint to the Department of Health and Human Services. If a minor is involved, file a report with Child Protective Services as well.

You can also share your experience with your elected officials. You can use your address to find your state legislators here.

Make a plan for next time

Early intervention is key to preventing a mental health crisis. Know your early warning signs and work with your mental health provider to create a plan for how to work through those early signs of mental health distress. One popular evidence-based program led by peer support specialists — people who have experienced mental illness themselves — which includes the creation of a personalized crisis plan is called WRAP (Wellness Recovery Action Plan).

Connecting with peer-run support groups and resources can be very beneficial to those with mental illness. People often say they feel less judged and more supported by others who can relate to their experiences. NC Health News has listed some local support groups, including peer-run groups, on our mental health resource page linked here.

- Designate a health care power of attorney

A person with mental illness can legally designate someone they trust to make health care decisions for them if they are unable to do so. This could be a useful tool for any adult patient, but could be particularly helpful for families with college-aged children. It allows for the voluntary admission of someone who may meet the involuntary commitment criteria, thereby providing a way to avoid the involuntary process in favor of a process that gives parents and patients more decision making authority over their treatment.

NC Health News often hears from parents of young adults who wish they could be more involved in their child’s mental health treatment, particularly during a crisis situation. This tool is something worth discussing with your child when they turn 18.

You can find North Carolina’s health care power of attorney form template on the N.C. Secretary of State’s website linked here.

- Fill out a HIPAA authorization form

In addition to designating a trusted family member or friend as a health care power of attorney, an individual with mental illness may also want to fill out a HIPAA authorization form, which allows health facility staff to release medical information and records to their health care power of attorney. This will ensure the designated people have access to the information they need.

There is a HIPAA release form template available on the American Bar Association’s website linked here.

- Create a psychiatric advance directive

Advocates encourage people with a mental illness to set up a psychiatric advance directive as a way to have their preferences taken into account during any subsequent mental health crisis, which may help avoid involuntary commitment. It’s a legal tool that allows an individual to instruct medical providers about what kind of treatment and medications they prefer — and which ones they do not — in the event of a mental health crisis. There is also a space to list the mental health facilities a patient prefers to go to if inpatient care is necessary. This legal tool has been available for some time and can be useful in helping guide providers if a patient is unable to clearly communicate their preferences.

As with the health care power of attorney, this tool allows for the voluntary admission of someone who may meet the involuntary commitment criteria, thereby providing a way to avoid the involuntary process. It gives a patient the ability to plan for an unwelcome but potential psychiatric event by writing down their prospective consent to treatment, including consent to voluntary admission to a psychiatric facility, in the event that they lose capacity to make treatment decisions during a mental health episode.

Creating a psychiatric advance directive can also help a designated health care power of attorney understand a patient’s wishes and advocate for them during a mental health episode.

You can find North Carolina’s psychiatric advance directive form template on the NC Secretary of State’s website linked here.

Alternatives to the emergency department

Start with your existing mental health provider, if you have one.

If you’re struggling with mental health issues and no one is in immediate danger, you may want to reach out to your mental health provider before going to the emergency room. There have been times when providers have recounted situations where they didn’t know their patient was struggling and later learned they went to an emergency room. In some cases, mental health providers might have alternative solutions to try before going to the emergency room.

Again, if the person experiencing symptoms of mental illness is not injured or in immediate danger, there are some other mental health crisis interventions. The following are some options you could explore or ask your existing health provider about.

- Call or text a crisis helpline

If you or someone you care about is struggling with mental health issues, you can always call or text the national suicide and crisis lifeline: 988. You’ll be connected to a counselor who will listen to your concerns, help de-escalate the situation, if possible, and direct you to some resources in your community.

Some additional mental health helplines are:

BlackLine 800-604-5841: a support line geared toward Black, Black LGBTQI, Brown, Native and Muslim communities.

Trans Lifeline 877-565-8860: a support line run by trans people for trans and questioning people.

North Carolina-based WARM line 833-390-7728: This mental health support line is staffed 24/7 by peer support specialists — people with their own experiences of mental illness — at Promise Resource Network in Charlotte. Other “warm” lines run by peer support specialists based in the United States can be found here. Many people find warm lines helpful because the person on the other end of the line can empathize and often can suggest resources for treatment or support.

- Call a mobile crisis unit

If you need in-person support from mental health professionals, you can call a mobile crisis unit to your home (or wherever you are) to help within an hour or two. (In the event of a drug overdose or injury, call 911 for immediate medical support.)

Mobile crisis workers can help de-escalate a person who is in crisis. They can provide in-person evaluations and help you determine next steps. You can search the number for a mobile crisis unit that serves your area by selecting your NC county on the website linked here, which is run by the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services. Also, if you call or text 988 and request a mobile crisis unit, they should be able to connect you to one.

- Go to a behavioral health urgent care

These are walk-in facilities for people in need of an immediate mental health assessment and referral to resources. You can find one in your area by selecting your N.C. county on the website linked here.

At time of publication, North Carolina has two peer-run respite centers for adults experiencing mental distress to voluntarily stay at for free for about a week and receive support from peer support specialists — people with lived experience of mental illness. There is one in Asheville and one in Charlotte. In Winston-Salem, there is a peer support group that can offer up to 24 hours of support for an adult during a mental health crisis.

There are a handful of child crisis centers — in Asheville, Charlotte and near Raleigh — that can support children in mental distress for short periods that do not require a patient to go through the emergency room for admission.

- Partial hospitalization or intensive outpatient therapy

These programs provide a less restrictive environment for intensive mental health therapies for people who wish to stay in their community and receive treatment. Consult with your health provider and/or insurance company to find an option in your area.