By Anne Blythe

North Carolina’s dental profession sometimes gets blamed for being too reluctant to make any changes to laws defining who can practice dentistry in the state in order to keep a tight lock on who gets licensed to provide oral health care.

Dental hygienists fought for years to have greater autonomy to practice without the direct supervision of a dentist on site until January 2020, when they gained some ground in that long-running scope of practice tug-of-war.

The state changed scope of practice rules for hygienists ever so slightly, giving those who work in public health settings the ability to clean teeth and do screenings even if a supervising dentist is not there to do a comprehensive look inside the patient’s mouth.

There could be more change, albeit incremental, coming to the dental profession if a bill making its way through legislative committees is approved during this General Assembly session.

Senate Bill 382, sponsored and filed by Republican Sens. Jim Perry (Kinston), Kevin Corbin (Franklin) and Todd Johnson (Monroe) with Democratic Sen. Gale Adcock (Cary), could give the North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners the authority to:

- Issue a dental license to an instructor from outside North Carolina who has logged 2,000 hours in clinical dentistry in the two years prior to their application for a license.

- Issue an instructor’s license to someone affiliated with a North Carolina dental school or academic medical center even if they are not licensed to practice in the state.

- Allow dental students to practice dentistry at long-term care facilities, group home programs and state and federally qualified health care facilities for lower income and underserved populations — if they’re accompanied by a licensed dentist.

- Allow the use of mannequins — rather than people — for the clinical assessment of dental students as part of the exams for licensure.

- Refuse to issue licenses to applicants to practice dentistry or be a hygienist if there is evidence of illness, substance use or mental health disorders, or physical abnormalities that would interfere with reasonable skill or safety. The proposal does not specify the illnesses or mental health disorders that might be applicable in such circumstances, but concerns were raised in public discussions about how questions about a mental health disorder could be stigmatizing.

- Require an applicant or licensee to submit to a physical or mental exam by licensed physicians or health care providers before a license is granted. The board also can insist on the same kinds of exams after disciplinary charges have been lodged or while investigating them. Failure to comply can be considered unprofessional conduct.

The bill was sailing through the legislative process in April, May and much of June. Now, it is in a conference committee where representatives from the House and Senate are trying to iron out differences before lawmakers head home for the year.

Evidence-based change

Gary Oyster, a Raleigh dentist who keeps up with legislative oral health initiatives for the North Carolina Dental Society, describes the bill as a bit of a catch-all. It definitely is not one that makes sweeping changes to scope of practice laws, Oyster acknowledged.

“The overriding concern is always patient safety,” Oyster said. North Carolina dentists, as a whole, look for substantial evidence to ensure that any changes will make oral health care better in the state, he added.

Critics have argued that dentists don’t want to cede ground to hygienists and others who might provide more access to oral health care, worried that the competition could cut into their profits.

“I feel like we’re open to things that have been proven to be beneficial to patients,” Oyster responded.

Some of the proposed legislative changes could bring needed care to some of the more underserved populations.

Steve Cline, interim vice president for the North Carolina Oral Health Collaborative, says the bill includes some of the changes his organization had hoped to see, but more could be done to help expand access to oral health care. He plans to work with the North Carolina Dental Society and others to get some of those changes through in coming legislative sessions.

“We decided we would do what we could this session, then keep the discussion going,” Cline said.

With many checks and balances in place, the legislation would give the state health director or someone tapped to fulfill the designated role the power to add facilities to the list where dental students can provide care, allowing for possibilities that might not be envisioned in the statute but still subject to review, approval or disapproval by the state board and dental schools.

In-state dental students already are allowed to help with care at long-term care facilities, area health education centers, hospitals, nonprofit health facilities and state or county health departments.

The law change would open the door to out-of-state dental students to do internships or externships in those places if the student submits written permission to the state dental board from the dean of the school they attend. They also need a written agreement from a licensed North Carolina dentist who will play a supervisory role.

What the numbers say

On the whole, North Carolina has 5.35 dentists per 10,000 people, according to 2021 data gathered by the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at UNC Chapel Hill. The rate varies widely depending on the county, though.

Five counties in eastern North Carolina do not have any dentist — Camden, Gates, Hyde, Jones and Tyrrell, according to the Sheps Center data. Orange County, home to the UNC dental school, has the highest rate of dentists — 19.1 per 10,000 people. Pitt County, the home base of the ECU dental school, has a little less than half that rate at 9.25.

Some counties, particularly those in the rural eastern part of the state, have seen a decline in the number of dentists over the past two decades. The urban centers around Mecklenburg and Wake counties have picked up more dentists, while the Triad region including Winston-Salem and Greensboro has not varied much during the 20-year period.

As many of the state’s dentists get closer to retirement age, North Carolina has not yet flooded the zone with a much greater number of dental school graduates.

Of the state’s 100 counties, all but six are dental care Health Professional Shortage Areas, according to a map created by the Rural Health Information Hub with data from the federal Department of Health and Human Services.

Portions of Wake, Chatham, Davie, Mecklenburg, Cabarrus and Union counties have shortages of dental care providers too.

Oyster said that part of the proposed legislation is designed to help the dental schools maintain robust instructor rosters.

“This bill had a lot of moving parts,” Oyster said.

New licenses, testing on mannequins

If the lawmakers push it through this session, and the governor signs it into law, the dental board could issue instructor’s licenses to dentists who come to the academic centers from out of state without a North Carolina license.

The instructor license would allow the dental school professors to work in clinical settings if they had experience and training from elsewhere that would put them in good standing.

Then if the instructor not licensed in North Carolina logged 2,000 hours, or about a year’s worth of 40-hour work weeks in the two years prior to submitting an application, they could be licensed to practice outside the academic settings. The proposed legislation is structured, Oyster said, to keep instructors from spending just a short time at an academic center, then leaving to set up a practice that might be more lucrative than teaching.

Dental schools across the country are recruiting professors and instructors out from under each other because of a workforce shortage, Oyster said.

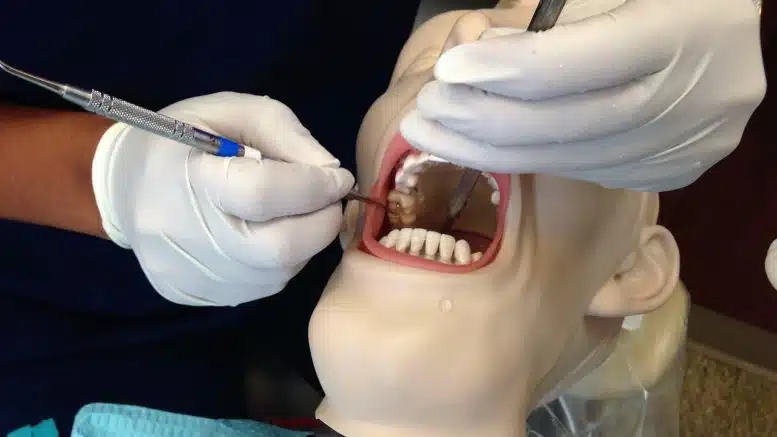

Other changes are afoot in the academic centers, including the use of mannequins in clinical exams for students.

For many years, the North Carolina dental schools required students to show their clinical mettle and expertise on live patients, something dental students often dreaded.

Then the coronavirus pandemic hit, and there were heightened concerns about exposure to COVID-19 and the state allowed for the use of mannequins during the state of emergency. Although there has been resistance to making that a perennial option, wider acceptance has grown among professors, students and licensing boards.

Sign up for our Newsletter

“*” indicates required fields

One often cited complaint about using live humans is the difficulty of finding a person whose oral health needs fit the bill. Extensive planning and preparation often is needed months before an exam.

That can also require extensive financial investment to get just the right patient, and to make sure they will be available on exam days.

Oyster said the mannequin exams have proven to be as rigorous as those on live patients, with more students failing than those who do skills assessments on real people. The dental schools make sure a student is ready to take on the tasks of the profession, and the state board is another safety net.

“We’re nimble and very flexible, but we always want to keep in mind what are the positive things about these changes and what are the negative things,” Royster said.