By Michelle Crouch

The Charlotte Ledger/ NC Health News

Emergency physician Jennifer Casaletto has been cursed at, shoved, punched, spat on and bitten while trying to do her job. One patient threw a container full of urine at one of her medical residents. Another kicked her when she was pregnant.

Violent incidents against health care workers have surged, Casaletto said, and she now tries to work mostly in large hospitals because they tend to have more security.

“In large emergency departments, you call security and they are there instantly,” said Casaletto, past president of the North Carolina College of Emergency Physicians. “Some of the smaller ones have security guards who have been told by the hospital they aren’t allowed to touch anyone. How does that keep us safe?”

A new state law aims to help address Casaletto’s concern. The legislation requires hospitals with emergency departments to have a law enforcement officer on site at all times, unless they get local authorities to sign off on an exemption. The requirement takes effect in 2025.

The law also calls for hospitals to report violent incidents to the state, to provide employees with violence-prevention training and to conduct a security risk assessment and create a detailed security plan.

The legislation is a response to an alarming rise in violence against doctors and nurses in North Carolina and across the country. Federal data show that health care workers are five times more likely to experience workplace violence than workers in other industries, and they accounted for 73 percent of nonfatal injuries from workplace violence in 2018, the most recent year for which statistics are available.

The rate of injuries from violent attacks against medical professionals grew by 63 percent from 2011 to 2018, the data show.

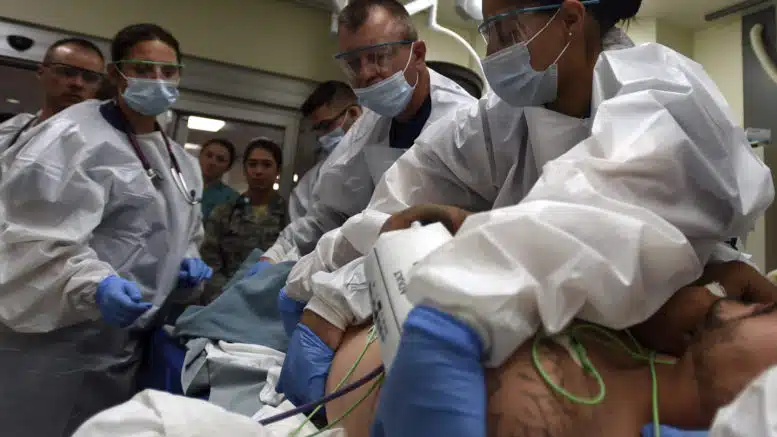

Emergency departments are particularly dangerous, since staff members are legally required to assess and treat anyone who walks in the door, even a patient who has been violent before. ERs also treat patients struggling with psychiatric problems and substance abuse, which can contribute to outbursts. Nationally, 55% of emergency physicians and 70% of emergency nurses report being physically assaulted on the job.

“The public has no idea what we have to endure.”

Violence in hospitals has long been an issue, but the coronavirus pandemic exacerbated the problem, hospital workers said. It sowed distrust between patients and care providers and contributed to a rise in bad behavior of all kinds among Americans. And hospital staffing shortages have contributed to long waits for care and frustrated patients.

The incidents against health care workers often go beyond threats or verbal assaults and result in serious physical harm to workers. For example:

- In July, a nurse at Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center in Charlotte was stabbed in the neck with a pen when he tried to help a colleague who was being attacked by a patient, Charlotte-Mecklenburg police said.

- At Duke Raleigh Hospital in 2022, a patient punched a nurse so hard that he knocked her unconscious and fractured her nose and eye socket.

- At New Hanover Regional Medical Center in Wilmington, a patient was charged with attempted murder in 2022 after he attacked two emergency room staff members, choking one until she fell unconscious and trying to snap the other’s neck.

One Charlotte nurse who asked not to be named told the Ledger/NC Health News that he “gets abused on a daily basis.”

“The public has no idea what we have to endure. There is tons of verbal abuse,” he said. “I’ve been attacked by a patient. One of my coworkers was kicked in the face and got knocked out.”

The increase in aggression and violence is driving doctors and nurses to leave health care settings they trained for, said Trish Richardson, president of the North Carolina Nurses Association.

“The violence feeds into significant burnout, which leads to staffing shortages, which exacerbates the frustration patients feel that can lead to violence,” she said. “It’s a vicious cycle; one feeds the other.”

A focus on prevention

Rep. Timothy Reeder (R-Ayden), a practicing emergency physician at ECU Health in Greenville, said he sponsored the bill because he has seen the effects of violence on hospital staff. “It’s personal for me,” he said.

Like many other states, North Carolina already had a law making it a felony to assault health care workers on hospital premises. But Reeder said when he investigated, he found that only a small number of people were being prosecuted, and he wanted to do more to protect physicians and nurses.

David McDonald, president of the North Carolina Emergency Nurses Association, said he is encouraged that the new law focuses on prevention, rather than just tougher penalties for offenders.

McDonald said nurses who have been assaulted don’t always want to file a police report because they worry about retribution or taking time off to go down to the station. In addition, he has heard that some hospital administrators discourage victims from pressing charges because they think it reflects poorly on the hospital’s public reputation.

“We are pushing hard on the prevention side to keep nurses from being assaulted in the first place,” he said.

“Don’t create a system that punishes.”

But some advocates for people with mental health issues feel the new law goes too far.

Corye Dunn, policy director for Disability Rights North Carolina, said that one big problem with bringing the hammer down on this behavior is that in some — if not many — instances, the behavior stems from an untreated mental health issue.

“While nobody thinks that violence in a health care setting is appropriate or acceptable, we have to be cautious that we don’t create a system that punishes people for seeking the care they need,” Dunn said.

She pointed out that frequently people who are involuntarily committed to psychiatric treatment will languish in emergency departments for days and sometimes weeks, which can create an explosive situation.

“People are staying in crisis longer because we are not able to get them the supports they need,” she said. “We are confining people in, for example, emergency departments, where they are deprived of natural light and fresh air in the name of waiting for a bed. We’re setting people up to fail as a system.”

Dunn worries that a bill like HB125 turns to “law enforcement to solve problems that are not criminal justice or law enforcement problems.”

Can law enforcement make a difference?

While some large North Carolina hospitals already have law enforcement officers on their campuses, Reeder said most rely on noncertified security guards or have no security at all.

Security guards have varying levels of experience and training. Some are former police officers or sheriff’s deputies with significant knowledge of de-escalation techniques and how to handle an active shooter situation. Others may have little to no law enforcement training.

Unlike a security guard, a law enforcement officer can make an arrest if necessary, said Eddie Caldwell, executive vice president and general counsel of the North Carolina Sheriffs’ Association.

“The people they’re dealing with, they know that if they don’t behave, they can be arrested and taken to jail,” he said, “whereas with a security guard, most people know that a security guard doesn’t have the authority to do that.”

To comply with the law, hospitals can hire off-duty law enforcement officers, contract with the county sheriff or the city police department to provide officers or create their own special police force, Caldwell said.

In Charlotte, Atrium Health said it has increased its security staffing in recent years, including adding armed guards with firearms and/or tasers. “Many have prior law enforcement experience or a military background,” the hospital said in a statement.

The guards would not meet the new law’s requirements, however, because they aren’t law enforcement officers with arrest powers.

Suzanna Fox, senior vice president and deputy chief physician executive for Atrium Health, said in a statement, “We know health care professionals work around the clock to provide quality care to everyone who needs it and they deserve to be protected from violence while they do it … We look forward to working with law enforcement in the communities we serve, as well as ongoing collaboration with lawmakers, to achieve greater safety for our teammates, patients and visitors at our facilities.”

Novant Health said it uses armed public safety officers as well as law enforcement officers on its hospital campuses. The system is still determining whether it will need to make changes to its current model, a spokeswoman said.

Benjamin Wiles is an emergency physician for the Novant New Hanover hospital system in Wilmington, North Carolina, which has its own police force. He said uniformed officers are stationed throughout the hospital, and he has noticed patients seem to behave better when they are nearby.

“If someone’s escalating, these guys are trained in de-escalation, and they’re very good at their job,” he said. “And so patients tend to react well to that.”

Reeder said some lawmakers and hospital officials expressed concerns about the cost of the law enforcement requirement, particularly for small rural hospitals that may struggle financially. That’s why the law includes a provision that allows hospitals to opt out as long as the local law enforcement agency signs off.

A spokeswoman for the North Carolina Healthcare Association, which advocates on behalf of the state’s hospitals, told the Ledger/NC Health News in an email that the association looks forward “to working with our elected leaders to determine how to best implement and modify the law to achieve our common safety goal.”

“Our top priority will always be ensuring that anyone who walks through our doors is confident that they are entering a safe and compassionate place to receive care,” the statement read.

Hospitals beef up security

Many hospitals across the state have already amped up their security to address the rising violence. Some — including Atrium Health, Novant Health and Duke Health — have installed metal detectors or weapon detection systems in their ERs.

Other safety steps include bolstering security staffing, making fewer entrances accessible, posting signs warning that assaulting a hospital worker is a felony and providing worker de-escalation training. (Click here to see the specific steps some N.C. hospital systems have taken to protect their workers.)

Making the ER safe for everyone

Casaletto, who went to the U.S. Capitol in 2022 to talk about the need for federal legislation to protect hospital workers, said she wishes the N.C. law didn’t have the “loophole” allowing hospitals to opt out of having an officer present, but she understands it could be a hardship for some rural hospitals.

She said she’s heartened that more hospitals are taking steps that they were reluctant to take just a few years ago, such as installing metal detectors and pressing charges.

Next, she said she wants to see more district attorneys prosecuting those who assault health care workers to the full extent of the law.

“These incidents aren’t just affecting emergency physicians and nurses,” Casaletto said. “They’re taking us away from our patients, and that makes everyone in the emergency department less safe.”

But Disability Rights’ Dunn said that without better mental health care in the community, beefed up enforcement might end up moving people who really need mental health care into the state’s carceral system instead, and they still won’t get the help they need.

“If we aren’t getting better outcomes, then maybe we should look at the systemic behaviors that are resulting in these outcomes,” she said.

This article is part of a partnership between The Charlotte Ledger and North Carolina Health News to produce original health care reporting focused on the Charlotte area. For more information, or to support this effort with a tax-free gift, click here.