By Jaymie Baxley

Many of North Carolina’s so-called rural counties bear little resemblance to the pastoral hamlets that people tend to picture when they think of rural living.

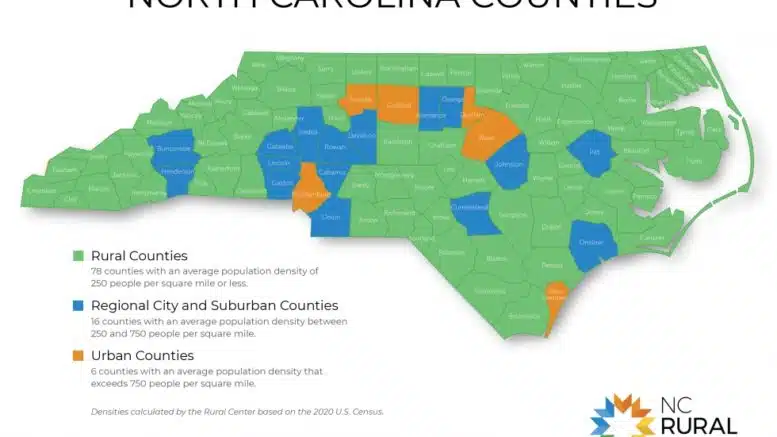

In reality, the 78 counties that fall under the common statistical definition of “rural” are home to about 40 percent of the state’s population, and North Carolina’s rural population is — next to Texas — the largest in the U.S.

The problems faced by these disparate communities can vary, especially when it comes to health care.

“I get asked all the time, ‘How is rural doing?’” said Patrick Woodie, president and CEO of the N.C. Rural Center. “My answer always begins by saying that it really depends on where in rural North Carolina you’re standing because it looks very different from different places. Different parts of the state have different challenges. In general, they’re all dealing with a lot of the same thing, but it looks a little different as you move around.”

Indeed, the main common denominator among the state’s rural counties is population density. A county is considered rural if it has 250 or fewer residents for every square mile of land, according to the criteria used by the N.C. Rural Center and other organizations. Despite that fact, of the state’s 78 rural counties, about 30 of them are part of metropolitan statistical areas, a designation used by the U.S. Census Bureau to delineate how socially and economically integrated those areas are with the “core” county.

“If you look at those 30 or so counties, from an economic vibrancy standpoint, they’re doing markedly better than some of our more isolated, rural parts of the state. Western North Carolina, in general, is doing markedly better than some of our communities along the I-95 corridor,” Woodie said.

For all of their differences, rural counties are disproportionately affected by certain issues. They have fewer residents with health insurance than their more densely populated counterparts. They are losing a higher percentage of people to drug overdose. In some cases, they are served by hospitals that are on the verge of shutting down.

While hardly new, those challenges came into sharper focus during the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same time, the global crisis spurred changes that may improve future health outcomes for rural North Carolinians.

“There’s good and bad that we’re learning from COVID,” Woodie said. “One of the positive highlights is we are seeing for the first time at a national level, and it’s also true in North Carolina, that the rural population is increasing after decades of, at an aggregate level, steady decline. We believe that it will not be an equal increase everywhere, but we do think it is a trend that is COVID-related.”

He added: “Everybody everywhere is rethinking their total approach to life, their approach to life-work balance and their approach to where they choose to live their life.”

At-risk hospitals

Eleven rural hospitals in North Carolina have either shut down or stopped providing inpatient care since 2005, according to data from the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research at UNC Chapel Hill. The only states that saw more closures over the same 18-year period were Texas and Tennessee.

Mark Holmes, director of the Sheps Center, said a record number of rural hospitals were expected to close across the U.S. before the federal Public Health Emergency, which took effect in May 2020 and expired earlier this month. That federal declaration provided a “lifeline” to struggling facilities in the form of provider relief funds, he said.

“We’re starting to ramp back up again this year,” he said. “Something that we’re constantly keeping an eye on is this concern that all these hospitals that probably would have closed in 2020 but were able to hold on for a couple of years are now out of support.”

He said that many of those hospitals could be closing in the coming 12 to 18 months.

The Center for Healthcare Quality and Payment Reform recently identified seven North Carolina hospitals that are at “immediate risk of closing because of the severity of their financial problems.” A 2022 report by N.C. Health News found that the state’s at-risk hospitals are largely based in rural counties that are poorer and have more racially and ethnically diverse populations than most rural counties.

Holmes believes the infusion of pandemic-related funding has contributed to a false impression that imperiled hospitals have achieved financial stability. While some of the state’s wealthier hospital systems saw record profits during the pandemic, the gains made by rural hospitals were not enough to lift them out of the red.

“There’s this notion, particularly in Washington, that hospitals had a record year and the rural hospital crisis is over,” Holmes said. “That narrative, we don’t believe, is an accurate representation of where we are. Rural hospitals, even though they got proportionately twice as much as urban hospitals, they’re still way below urban hospitals in terms of survivability.”

Substance use

The opioid epidemic has taken an outsize toll on the state’s rural communities.

An N.C. Health News analysis of substance use data from the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services found that rural counties accounted for 42.6 percent of drug overdose deaths reported across the state in 2021, the latest year for which complete data is available. About 30.6 percent of that year’s fatal overdoses were linked to suburban counties, while 26.7 percent were connected to urban counties.

The landmark national settlement with drug companies that abetted the epidemic is set to provide state and local governments with money to bolster services for people who struggle with substance use. Payments from the state’s $750 million share of the settlement, which will be dispersed in chunks over the next 18 years, began last May.

But Loftin Wilson, programs manager for the North Carolina Harm Reduction Coalition, said there are still “way fewer resources in rural counties than in the city.” His organization, which focuses roughly half of its operations in rural communities, is attempting to bridge the gap by bringing services directly to individuals with substance use disorders.

“All of our rural programs are completely mobile, and they’re based on a delivery system where folks reach out to an outreach worker and the outreach worker comes to them instead of them having to go to a brick-and-mortar space,” he said. “That helps to address both transportation barriers, which are rampant in rural areas, and also the stigma of drawing attention from people who don’t like what we do, which can create sort of an intimidating environment for people in small towns and rural areas where everybody knows everybody.”

Wilson said the coalition and similarly minded organizations have received “a lot of backlash” from critics who question the effectiveness of services that seek to minimize the toll of substance use. Common harm-reduction strategies such as providing clean syringes to people who are not yet ready to enter recovery, he said, are sometimes viewed as “unacceptable” alternatives to programs that ask clients to stop using altogether.

“The idea of having a non-judgmental space where there is no pressure to reach abstinence from drug use can be very counterintuitive to people because we have an abstinence-based culture and attitude toward drug use in general,” Wilson said. “It can be kind of shocking for people who are first introduced to the idea that there are spaces and services where the goal is not necessarily to help people reach abstinence from drug use but to help people improve their health and well-being, whatever that looks like for them.”

Health insurance gap

Rural North Carolinians are 40 percent more likely to be uninsured than residents of urban counties.

Medicaid expansion will go a long way toward addressing that disparity. Signed into law by Gov. Roy Cooper in March, the expansion will provide coverage to about 600,000 people who currently lack health insurance. Many of those people are low income workers such as farmers, pastors, day care workers and others earning less than about $41,000 for a family of four.

“It disproportionately will affect working, rural people who do not have health insurance and cannot afford it,” said Woodie, the Rural Center president. “That will be a game changer.”

Expansion, he added, will have a “major economic-development impact” on rural communities. In terms of magnitude, Woodie said it is on par with the auto company VinFast’s plan to build an electric-vehicle factory that will bring 7,000 jobs to Chatham County.

“Medicaid expansion is a huge plus and a huge victory,” he said. “We should feel good about it. But boy, do we have our work cut out for us.”

Arguably the biggest challenge is ensuring that newly insured people in rural areas have access to health care services. Rural counties have historically suffered from a dearth of providers, with the Sheps Center estimating that there are only 13 physicians for every 10,000 residents in rural North Carolina. Urban counties, meanwhile, have an estimated 36 physicians for every 10,000 residents.

Credit: Sheps Center for Health Services Research, UNC Chapel Hill

“One of the things we’re most excited about in the next few years is seeing how Medicaid expansion can have an impact on people’s access to health care in general, particularly when it comes to medication for opioid use disorder,” Wilson said. “Most of our participants, not all of them by any means, but a majority of them are uninsured, and having access to health insurance would be transformative in terms of not only substance use disorder but many different issues.

Sign up for our Newsletter

“Many people have other chronic health conditions often that they’re managing, so just having access to health care or even primary care would improve people’s quality of life.”