By Rose Hoban

Year after year, nurses top the list of the most trusted professions.

At the same time, politicians rank at the bottom when it comes to the public’s trust.

That fact didn’t deter nearly three dozen nurses from participating in a program earlier this year to prepare them to run for public office. Thirty-four nurses gathered in Durham to take part in Healing Politics, a campaign school for nurses interested in serving their communities outside the clinics, hospitals and health care offices where many of them work.

In North Carolina, where Medicaid expansion and other health-related issues are hot topics of debate, health care workers don’t always have a seat at the tables of power where crucial decisions are made that have an impact on the everyday lives of North Carolinians.

“It wasn’t until I became a nurse that I realized how very important it was to pay attention and watch what was going on in our state and federal legislatures, because it’s directly related to my practice,” said Kimberly Gordon, one of the founders of Healing Politics.

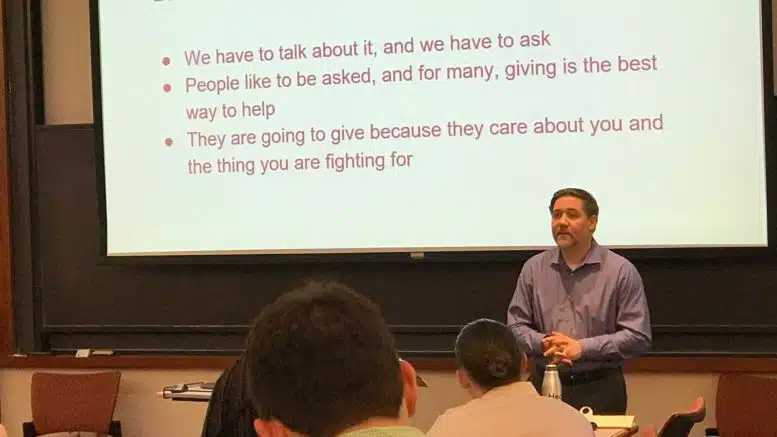

The three-day event, held at Duke University’s Sanford School of Public Policy, covered topics such as campaign planning and fundraising, communications and media strategies, ethics and getting out the vote. It’s billed as the first program in the country with the specific purpose of motivating, inspiring and training nurses and midwives to seek office up and down ballots.

(Disclosure: This reporter taught a section on effective interaction with the media at the campaign school.)

Gordon, a certified registered nurse anesthetist from Winston-Salem, wasn’t too involved in the political process until she was a graduate student. Studying for her doctorate at Yale’s nursing school, she created the curriculum as part of her capstone project, working with her faculty adviser Lisa Summers, who has since retired.

“Health care is not a solitary sport. We work in teams. We base what we do in evidence, we value science. We have a process. Nurses evaluate the evidence, we evaluate the problem, we create a plan, we implement it and then we circle back around and say, ‘Did that work?’” Summers said. “That’s the way we think, which is a wonderful way of thinking to bring to a legislature.”

In a time where politics has become more fractured than ever, Gordon and Summers believe that nurses have a message that’s relevant across party lines and social divisions. That’s part of the reason they’re calling their campaign school “Healing Politics” and talking to nurses about their potential role in policymaking.

“When you take care of your first homeless patient, or you have somebody who can’t read a consent form that you need them to sign, all of a sudden it becomes crystal clear that all of the policy that’s made in state, city, federal legislatures, it really does affect people, and especially the most vulnerable among us, which, unfortunately, oftentimes are our patients.”

Kimberly Gordon, co-founder of Healing Politics

Developing campaign pitches

One of the most daunting prospects for any potential candidate is fundraising. During one of the workshop sessions, participants were paired and told to look one another in the eye, shake hands, give their campaign pitch and ask for a donation.

“Hi, I’m So-and-So, I’m a nurse running for the town council because I have a vision of our town being a healthier place to live. Can I count on your support with a donation of $50?” was a sample pitch script.

Some participants made donation requests that were much higher. But even making the ask was a tough task for many.

“I am not comfortable talking about myself and bragging about my accomplishments,” said Dorie Kogut, a nurse from Winston-Salem. The lesson she learned at the campaign school, Kogut said, was that she’s not yet ready for a run for office.

“If I wanted to go into politics, it would be something at a local level, but nothing grandiose,” Kogut added.

Others came away more determined to launch a campaign. Peggy Wilmoth, who lives in Chapel Hill, spent 35 years in the military and stayed out of politics while she rose to the rank of major general.

“I retired six years ago, and that is when I’ve been able to begin to make a move to become more politically involved and seriously consider running for office,” Wilmoth said. “The practicing of asking and explaining myself and why I want to run is really my biggest takeaway so far.”

Sybil Shepherd Harrington from Holly Springs said she had positive interactions with the governor’s office during Gov. Pat McCrory’s administration, an experience that led her to think she could make a positive difference in elected office.

“I don’t want to just complain about things,” Harrington said. “I want to be able to get things done and also have solutions for them.”

Specialized campaign schools

Campaign schools are designed to give political neophytes the skills and knowledge they need to make an initial run for office. North Carolina has long had a well-regarded campaign school in the nonpartisan Institute for Political Leadership, which was started in 1974 in Wilmington. It was unique in the state, but over the past few decades such programs have proliferated across the nation.

“There are over 700 campaign schools now, and all sorts … for women, for veterans, a lot of LGBTQ and underrepresented — those are newer ones that we’re really starting to see,” Gordon said. “And most of the parties in states will run their own.”

North Carolina is somewhat unusual in that it already has five nurses in the state legislature, but campaign consultant James Hagger said that’s becoming more common. His home state of Minnesota has four nurses in the legislature.

Nurses, with their training and attitudes, “make great elected officials and make great candidates,” Hagger said.

“They have a toughness to them, they have an ability and a desire to do hard work,” said Hagger, who ran nurse-legislator Erin Murphy’s unsuccessful 2018 campaign for Minnesota governor. “They have an honesty to them. And they’re used to working in teams, they’re used to working through challenges and finding good solutions and good outcomes. They’re dedicated and caring about the work that they do, and they’re not afraid to kind of dig in.”

That kind of willingness to work in teams is much-needed in today’s political landscape, and it makes for a desirable candidate, Hagger added.

A variety of civic engagement ideas

Gordon said that while the American Medical Association has had a campaign school for physicians for decades, there’s no equivalent for nurses. That’s why Gordon and Summers, whose Yale research was on the representation of nurses in elected office, decided to create a campaign school themselves.

The inaugural Healing Politics workshop was supposed to happen in May 2020, but the pandemic derailed that plan. So the two women waited and dug in. Meanwhile, Summers’ connections across academia came in handy, especially at Duke University with political science Professor Nick Carnes.

“His body of research was looking at nontraditional candidates and why more nontraditional candidates didn’t hold elected office,” Summers said.

Carnes facilitated bringing Healing Politics to Duke’s Sanford School of Public Policy, and he, Gordon and Summers will study the outcomes for participants over the next five years. In their study, the measure of success isn’t just running for office.

“It might also be becoming more civically engaged, maybe becoming engaged in their nurses associations, community organizations,” Gordon said. “Along with getting them to vote, getting them to advocate for the profession or patients. So we’re looking at many different metrics of what success looks like.”

Some of the preliminary results are surprising, Gordon said.

Sign up for our Newsletter

“*” indicates required fields

“What we learned is that women, when they go to a campaign school, even if they decide not to run, they become more civically engaged,” Gordon added.

That could be seeking and winning a seat on a state health committee, getting involved in a town task force or volunteering for board service.

At least two of the inaugural program’s participants are planning to seek elected office in 2024, according to Gordon, including one of the five North Carolina nurses in the Durham class.

“Even if we don’t get 30 out of those 34 people to run, I feel like we’re already moving the needle,” Gordon said.